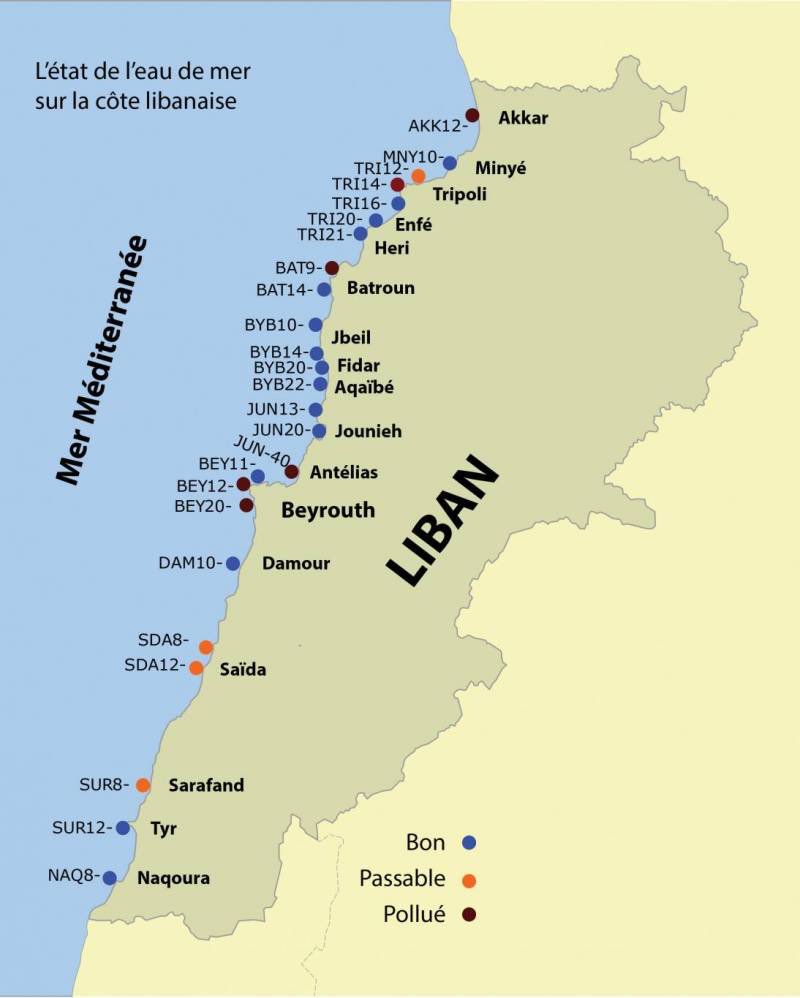

In recent weeks, two seemingly contradictory studies were presented to the public concerning the state of Lebanon’s beaches: One, by LARI, warning that the country had “passed the threshold of pollution and that no sea is pollution free,” and the other, by CNRS, casting doubt on the results of the former.

LARI, the Lebanese Agriculture Research Institute’s findings triggered a wave of public outrage and panic. And news headlines in the days that followed (like al-Akhbar’s “No region in Lebanon is free of pollution: Farewell to swimming” and The Daily Star’s “Do not swim: Coastal water pollution getting worse,” as well as a recent CNN report) clearly didn’t help.

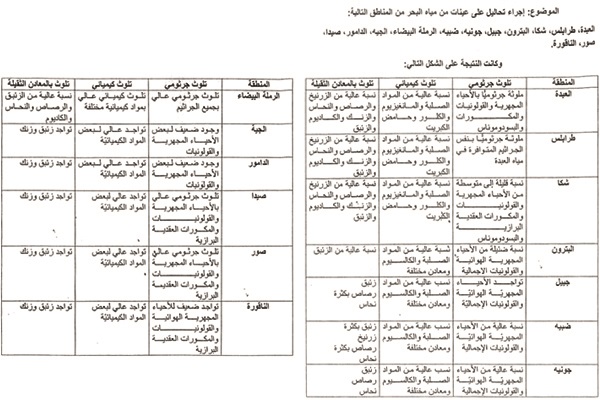

In the wake of LARI’s study, CNRS brought another set of findings to the table. According to the National Council for Scientific Research, just under one-fifth of Lebanon’s coastal areas surveyed were found to be polluted and unsuitable for swimming.

“The situation is critical, but not hopeless,” CNRS’s Secretary General Mouin Hamza told The Daily Star in a follow-up article.

Confused about the situation, I decided to ask marine biologist Jina Talj for clarity. The dedicated sea-lover, who also runs the NGO Diaries of the Ocean, thinks that panic benefits the few.

“LARI’s study is not comprehensive, they did not present to us the full report nor the methodology in terms of how many samples were taken, where from, during what period etc. They showed us a table that has no source, no numbers, no percentages – a table that classified magnesium, calcium, and chloride as chemical pollutants, which to be honest is ridiculous.

There is no need for all this drama, the status of our beaches is pretty much the same compared to previous years. According to the CNRS study, Tyre and Naqoura are clean and so are Batroun and Kfarabida and a few other areas seen on the map. Anything between Shweifat and Tabarja is highly contaminated.”

“So why was the public presented with such alarming findings right before beach season?” I asked.

“I think there is an attempt to raise fear and push people toward resorts in general, now that there’s a lot of hoopla against resorts,” Talj said.

Lebanon has been grappling with a neverending waste management crisis for many years. In 2016, the government’s solution to that crisis was a temporary fix to dump waste from Beirut and Mount Lebanon in two new coastal landfills, in Bourj Hammoud and Costa Brava. The garbage in those two landfills is neither sorted nor treated in a manner that takes the environment into account. As a result, the garbage that makes its way into the sea is carried by a gyre called the Shikmona Eddy–a circular current in the Mediterranean that regurgitates whatever is introduced to it back onto the shores and onto international news headlines.

Apart from that, some environmentalists say that ninety percent of Lebanon’s wastewater that includes sewage as well as chemical and other toxic material goes untreated to the sea.

But while people suffer and protest, others use it to their own benefit, and in that respect, there might be a lot of truth to what the marine biologist is saying. In recent years, Lebanon’s coasts have been usurped by developers who in more than one way take advantage of the deteriorating conditions of the coast and public apathy.

Seeing opportunity where others see disaster, developers in recent years have built resorts that cater to the rich and well-off. Their close ties to Lebanon’s ruling elite allows them not only to illegally take over public spaces through schemes and dubious decrees but to redirect sewage pipes elsewhere, particularly to areas that are disadvantaged and whose folks live below the poverty line.

This strategy clearly paid off during the take-over of Beirut’s last public beach in Ramlet el-Bayda. Although activists put up a fierce fight, resistance was scant when compared to the scale of the problem. There were even counter-protests by those who were promised and given jobs at the resort that was built on the beach’s shores and its opening saw famous faces come and celebrities endorsing the project.

The fight for Lebanon’s beaches continues as real estate moguls pursue other takeovers. Anfeh’s historic salt marshes and Kfarabida beach in Lebanon’s north are still under threat, and in Lebanon’s south, conservationists are still fighting to preserve one of Lebanon’s only turtle sanctuaries. To protect what is left of this country’s coast, it is incumbent on citizens to take up responsibility, by first holding those in power accountable, and holding ourselves to a higher standard. Yes, huge sections of our coast are polluted, Talj admits, but if given the chance they can recover.

“If given the chance and if a proper waste management plan is implemented and the sources of pollution removed, Lebanon’s dirty beaches can recover in a matter of weeks especially in terms of organic waste. Chemical waste is more challenging as it bioaccumulates in sea animals and goes up the food chain.

If you see trash on the beach, pick it up, take it upon yourself to not give them [developers] an excuse to take over our beaches. Participate in campaigns to raise awareness, and join protests to protect our coasts when you can. It’s all we’ve got left,” Talj stressed.

As for how long we can maintain what’s left of the very few clean public places, it is important to keep a positive outlook so as to not give up, she said.