Many of you have heard of the endeavored usurpation of the Kfarabida beach by now. In fact the Newsroom Nomad has mentioned it quite a few times in a blog post, and on our various social media pages. We also joined civil society groups and environmentalists who headed to the protest scene last Saturday to denounce the planned luxury resort that will see the inundation of maritime property –using tons of cement– to make way for mid-water bungalows and accompanying wave-breakers -a hazard to the precarious biodiversity and sea-life in the region.

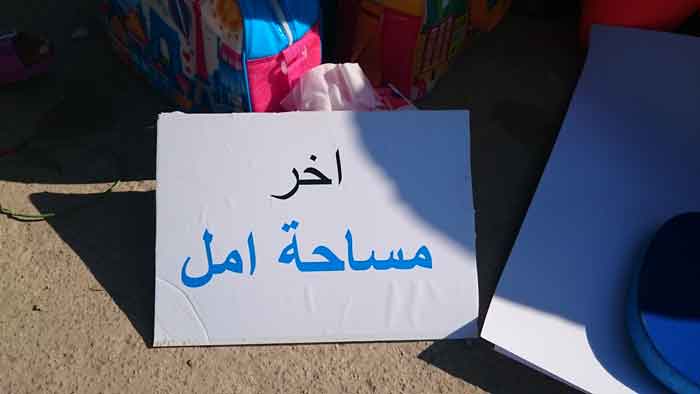

أهالي كفرعبيدا: لن تأخذوا شاطئنا

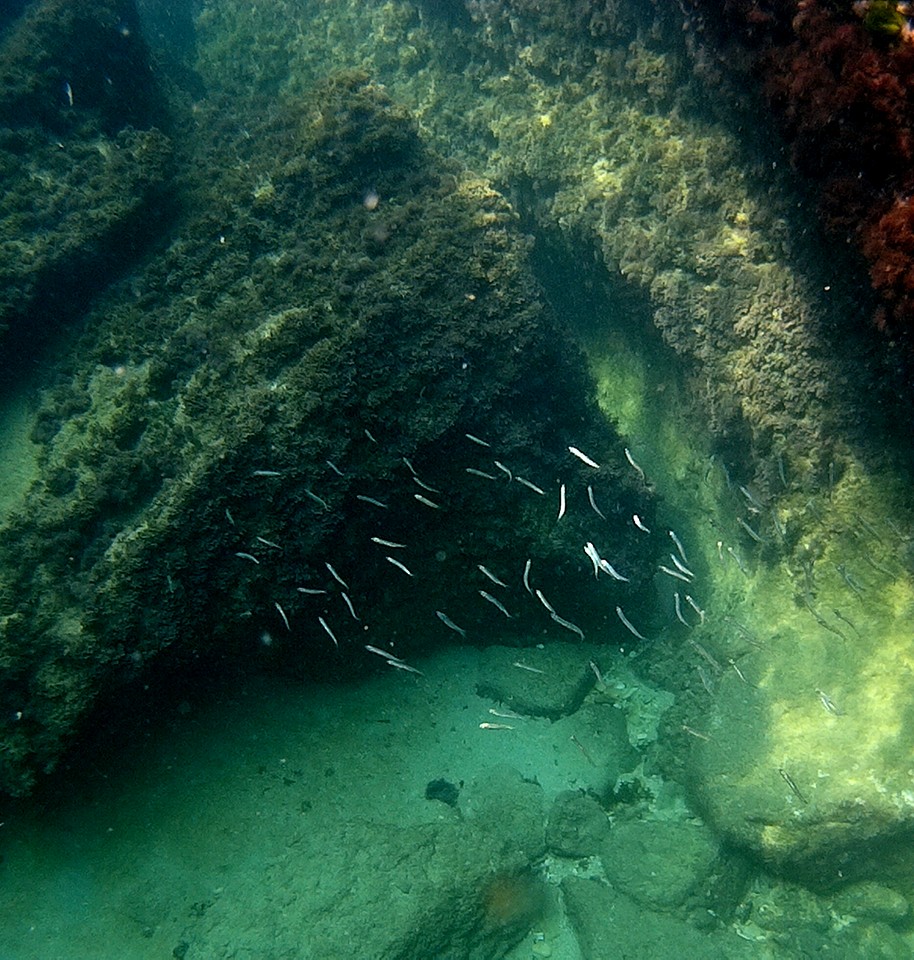

For all those unaware, Kfarabida (like Aadloun, Dahlieh, and Ramlet al-Baida) is one of Lebanon’s only remaining public shores that has yet to be taken over by developers abetted by the Lebanese authorities. Only unlike the Ramlet al-Baida beach, which is deliberately being kept polluted, Kfarabida boasts one of the country’s cleanest waters –home to ancient caves, corals, sea turtles, and other marine animals– a conviction that divers, swimmers, the Lebanese Council for Scientific Research (CNRS), and these photos can attest to.

To say that the protest on Saturday was prodigious would be propaganda. To my disappointment, there were an estimated 100 people there during the main hours of the protest. I was later told by organizers that over a thousand signatures were collected on the petition papers, which suggests that many were coming in to sign rather than remain for prolonged periods. Nevertheless, the litter on the shore was overwhelming; a fact that was left unaddressed save for the effort of a few volunteers who took it upon themselves to collect the accumulated trash -myself included. In fact, this blog post would have been published a few days earlier had I not caught a bug in the process.

In a bid to understand why this area is seemingly neglected and why some were supporting the project, I set out asking questions to neighboring households, and market owners. Although the answers weren’t surprising, they were disappointing nonetheless.

According to one market owner, who spoke on condition of anonymity and whom we will refer to as “Wissam”, there are deeper dynamics at play.

Politics and Civil War wounds

“This isn’t about environmentalism, but about politics. People here do not believe the organizers of the protest; the town is split between opponents and proponents especially in terms of the political groups behind each team,” he said.

“The Free Patriotic Movement, namely Foreign Minister Gibran Bassil, is opposing the project, while fellow Batroun MP, Telecoms Minister Boutros Harb is supporting it, and people do not change their allegiances overnight, not when the wounds of war have yet to heal.”

The “wounds” he refers to reflect back to a time when Syrian Forces made their presence heavy. During the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990) Kfarabida, like many other areas across the country, was divided between those who saw allies in the Syrians and those who fought against them. Many lives were lost during that period, and many homes were unwillingly abandoned as people fled and ultimately immigrated.

“The people have not forgotten … I have seen grown men tremble at the sight of a checkpoint. It doesn’t matter if the checkpoint now belongs to the Lebanese Army, their trauma does not allow them to see past the barbed wires … the years that have passed don’t matter. Memories are still very much alive.”

The Lebanese Civil War ended in 1990, and the Syrian Forces withdrew in 2005, but political rivalries between pro-Syrian groups (the March 8 camp to which Bassil belongs), and staunch opponents (March 14, which Harb is a part of) are still present. This prevents many people from joining protests that are seen to be supported by one political group and not the other, even at the cost of the environmental treasure that is the Kfarabida shoreline.

“If Bassil had been given a cut of the profit, you wouldn’t have seen a protest here today.”

Poverty

In the years that followed the end of the Lebanese Civil War, Kfarabida never really did see (like many of its counterparts) any kind of compensation or apt rehabilitation and development. Many of its natives are impoverished and see the resort as a developmental project that could reflect positively on their livelihoods.

“The people here desperately need jobs, we need some sort of development to revive our stagnant economy,” Wissam says, “the only way to bank from this project is to build in the sea… everyone is doing it, even the locals!”

Environmentalists opposing the resort have repeatedly said that they are not against the construction of the project itself, but are against illegal land reclamation and the usurpation of the maritime property –a detail Wissam dismisses as falsehood.

“If the land and sea are not developed, then the property will be sold to a new buyer, whom most probably will be a politically influential Muslim with the ability to get past all these nuances. We don’t want that to happen … the land is currently owned by a Christian who acquired it during the Civil War when the government was bankrupt… Kfarabida is a predominantly Christian town and we would like to keep it that way. We have already lost too much.”

Fear and poverty feed oligarchy, secure elections

It is a well-known fact that fear of the other, deprivation and reliance on political groups, feed oligarchy and secure elections. But what they also do is keep people in controlled artificial scarcity. This has a grave impact on the environment, as the poorer a population is the more inclined it is to put pressure on the land. This can be seen in frenetic construction in general, shoreline included, as well as deforestation for charcoal manufacturing and for the production of agriculture. Water mismanagement, sand and stone quarries and other industries are also largely run by politicians and their affiliates who bank on the profits while destroying the environment. Why there is little opposition to these trends is mainly due to the people’s reliance on these industries. Without them many would be unemployed and unable to provide for their families. Any opposition would also result in their dismissal. Their allegiance generates their income. This is the malignant symbiosis between poverty and oligarchy to speak in general terms, and this is why:

Environmentalism and politics don’t mix

Almost every time a protest has occurred in Lebanon, it has been suspected of being politically motivated by one side or the other. While there may be some truth to that, it is of no direct fault of many activists who join out of a pure motivation to save what is left. However, the harsh reality is that most protesters are seen as pawns in a turbulent sea of political ebbs and flows where people hold no power nor are they given an electoral voice. Will this reality continue to gnaw at what’s left of Lebanon’s environmental treasures? If mistrust persists to be a reigning reality, then in all honesty I do not know how this will be averted. In the words of Human Rights Watch’s Nadim Houry, Lebanon cannot move forward without adequately dealing with its past. Kfarabida is a prime example of that.

Too bad that Wassim was not the right person to talk to, especially that all of us while reading this article knew exactly who that Wissam is. Pleaseeee when you need locals points of views it’s better to have more than 10% of the population point of views. The protest has nothing about politics . It has nothing with Gebran Bassil and Boutros Harb. Laws are laws and we will not change our mind. We will not accept the privatization of The beach and of the caves. The other mission behind the protest is ecological and don’t care if people trust or not. We do trust ourselves and this is important .

Thanks for your feedback Rita, however I would like to point out that I did speak to over ten people who were not present at the protest to try and get a broader idea as to why they weren’t. Most echoed the same fears and some even became extremely defensive and patronizing that I simply had to cut the conversation short. If you will go through my blog you will notice that I do not care much for politicians, but rather for the environment and the well-being of the people, but still feel that it is vital to point out why such dynamics exist. The case of Kfarabida is similar to many towns and villages across Lebanon, the Jannah dam for instance (where many people blocked roads to voice their support for the project). In any case I wish you luck and do hope, for your sake and ours, that you are successful. You have my utmost respect.

Hello dear,

I want to clarify some points:

This beach is receiving hundreds of visitors every week and the municipality is completely absent with no special place for trash bags, no control, no police . It’s so evident to have so much garbage in a place where it’s own municipality is absent. Who do you think will take care of your beach more than yourself ?

After our peaceful protest we left the place much more cleaner than when came. We have cleaned the beach coast and have gathered more than 50 big trash bags. And we moved what we could in our private cars and we kept the remaining to the municipality. And on monday the municipality removed what was left after we called them to do so.

We have collected more than 1200 signatures during our “on site petition ” on sept 10th. Which it means that this number is far away from the mentioned 100.

And only the people who came via the sea , in their own boats are even more than 100.

https://www.facebook.com/events/641487512694824/permalink/647185685458340/

All the black bags and the small ones where removed in our private cars.

Hello Clara, good to hear from you. First and foremost, thank you for all your efforts; I do hope that they will yield the much needed results. As for the trash, I did mention that volunteers participated in the clean-up, though I did camp till the next day where friends and I were still struggling with mounds of uncollected litter. We packed over 30 bags alone and had to carry them up the road where an old municipality worker was picking them up. We even tried contacting the municipality as we were completely out of energy and could no longer do it, but received no answer. As for the number of signatures I will add that to the blog post. I was referring to the given number of participants during the main protest, as it now seems clear that many were dropping in to sign and leave. Thank you for that.